1. TO BEGIN

Read the poem all the way through at least twice. Read it aloud. Listen to it. Poetry is related to music, so the sound is important. You listen to your favourite CDs many times; the principle is the same. It takes time to fully appreciate and understand a work of art. Make a note of your first impressions or immediate responses, both positive and negative. You may change your mind about the poem later, but these first ideas are worth recording.

2. LITERAL MEANING AND THEME

Before you can understand the poem as a whole, you have to start with an understanding of the individual words. Get a good dictionary. Look up, and write down, the meanings of:

• words you don’t know

• words you “sort of know”

• any important words, even if you do know them. Maybe they have more than one meaning (ex. “bar”), or maybe they can function as different parts of speech (ex.

“bar” can be a noun or a verb). If the poem was written a long time ago, maybe the history of the word matters, or maybe the meaning of the word has changed over the years (“jet” did not mean an airplane in the 16th century). An etymological

dictionary like the Oxford English Dictionary can help you find out more about the history of a particular word.

Use an encyclopaedia or the Internet to look up people and places mentioned in the poem. These allusions may be a key to the poet’s attitudes and ideas.

As you pay attention to the literal meanings of the words of the poem, you may see some patterns emerging. These patterns may relate to the diction of the poem: does the poet

use “street talk” or slang, formal English, foreign language phrases, or jargon?

Your goal, now that you’ve understood the literal meanings, is to try to determine the theme of the poem – the purpose the poet has in writing this poem, the idea he wants to

express. In order to discover the theme, however, you need to look at the poem as a whole and the ways the different parts of the poem interact.

3. TITLE

Start your search for the theme by looking at the title of the poem. It was probably carefully chosen. What information does it give you? What expectations does it create?

(For example, a poem called “The Garden of Love” should cause a different response from the one called “The Poison Tree.”) Does the title tell you the subject of the poem (ex. “The Groundhog”)? Does the title label the poem as a specific literary type? (ex. “Ode to Melancholy”; “Sonnets at Christmas) If so, you should check what characteristics such forms have and discuss how the poet uses the “rules.” Is the title an object or event that

becomes a key symbol? (see Language and Imagery)

4. TONE

Next you might consider the tone. Who is peaking? Listen to the voice. ? Is it a man or a woman? Someone young or old? Is any particular race, nationality, religion, etc.

suggested? Does the voice sound like the direct voice of the poet speaking to you, expressing thoughts and feelings? Is a separate character being created, someone who is not necessarily like the poet at all (a persona)? Is the speaker addressing someone in particular? Who or what? Is the poem trying to make

a point, win an argument, move someone to action? Or is it just expressing something without requiring an answer (ex. A poem about spring may just want to express joy about the end of winter, or it may attempt to seduce someone, or it may encourage someone to go plough in a field. What is the speaker’s mood? Is the speaker angry, sad, happy, cynical? How do you

know?

This is all closely related to the subject of the poem (what is the speaker talking about?) and the theme (why is the speaker talking about this? What is the speaker trying to say about this subject?).

5. STRUCTURE

How is the poem organized? How is it divided up? Are there individual stanzas or numbered sections? What does each section or stanza discuss? How are the sections or

stanzas related to each other? (Poems don’t usually jump around randomly; the poet probably has some sort of organization in mind, like steps in an argument, movement in time, changes in location or viewpoint, or switches in mood.) If there are no formal divisions, try breaking down the poem sentence by sentence, or line by line. The poet’s thinking process may not be absolutely logical, but there is probably an emotional link between ideas. For example, you might ask a friend to pass mustard for a

hotdog and suddenly be reminded of a summer romance and a special picnic. It doesn’t look rational from the outside, but it makes emotional sense.

A very controlled structure may tell you a lot about the poet’s attitude toward the subject.

Is it a very formal topic? Is the poet trying to get a grip on something chaotic? A freer poetic form is also worth examining. What is appropriate or revealing about the lack of structure?

6. SOUND AND RHYTHM

Poetry is rooted in music. You may have learned to scan poetry-to break it into accented/unaccented syllables and feet per line. There are different types of meter, like iambic pentameter, which is a 5-beat line with alternating unaccented and accented

syllables. You can use a glossary of literary terms to find a list of the major types of meter.

Not all poems, however, will have a strict meter. What is important is to listen to the rhythm and the way it affects the meaning of the poem. Just like with music, you can tell if a poem is sad or happy if you listen carefully to the rhythm. Also, heavily stressed or repeated words give you a clue to the overall meaning of the poem.

Does the poem use “special effects” to get your attention? Some words take time to pronounce and slow the reader down (ex. “the ploughman homeward plods his weary way” echoes the slow plodding pace). Other words can hurry the reader along (ex. “run

the rapids”). If you are unfamiliar with the terms alliteration, assonance and onomatopoeia, you can look them up and see if they apply to your poem-but naming them is less important than experiencing their effect on the work you are examining.

Does your poem rhyme? Is there a definite rhyme scheme (pattern of rhymes)? How does this scheme affect your response to the poem? Is it humorous? Monotonous? Childish like a

nursery rhyme? Are there internal rhymes (rhymes within the lines instead of at the ends)? If you read the poem aloud, do you hear the rhymes? (They could be there without being

emphasized.) How does the use of rhyme add to the meaning?

Certain poetic forms or structures are supposed to follow specific “rules” of rhyme and meter (ex. sonnets or villanelles). If you are studying a poem of this type, ask yourself if the

poet followed the rules or broke them-and why.

Different parts of a poem may have different sounds; different voices may be speaking, for example. There are lots of possibilities. No matter what, though, the sound should enforce

the meaning.

7. LANGUAGE AND IMAGERY

Every conclusion you have drawn so far has been based on the language and imagery of the poem. They have to be; that’s all you have to go on. A poem is only words, and each

has been carefully chosen. You began by making sure you understood the dictionary meanings of these words (their denotative meaning). Now you have to consider their visual

and emotional effects, the symbols and figures of speech (the connotative meaning).

Look for the concrete pictures, or images, the poet has drawn. Consider why these particular things have been chosen. If an owl is described, does that set up a mood, or a time of day? If a morning is called “misty”, what specific effects does that have? Are

certain patterns built up, clusters of words that have similar connotations? For example, descriptions of buds on trees, lambs, and children are all pointing toward a theme involving spring, youth and new birth.

Symbolism is also often used in a poem. A symbol is an event or a physical object (a thing, a person, a place) that represents something non-physical such as an idea, a value, or an

emotion. For example, a ring is symbolic of unity and marriage; a budding tree in spring might symbolize life and fertility; a leafless tree in the winter could be a symbol for death.

Poets use techniques and devices like metaphors, similes, personification, symbolism and analogies to compare one thing to another, either quickly and simply (“He was a tiger”) or

slowly over a stanza or a whole poem (an extended metaphor like this is called a conceit).

(You can check the Vanier Exit Exam Guide for explanations of common techniques and devices.) Work out the details carefully. Which comparisons are stressed? Are they all

positive? How are they connected? A description of birds flying could have any number of meanings. Are the birds fighting against the wind? Soaring over mountains? Circling a

carcass? Pay close attention and pick up the clues.

Poems, like music videos and movies, employ a series of images and symbols to build up mood and meaning. You need to take time to feel the mood and think about the meaning. If you have specific problems or poems to consider, come to The Learning

Centre, speak to your teacher, or ask at the library for books that will help.

Now that you have considered some of the key elements of the poem, it is time to step back and decide what the poem means as a whole. To do this, you need to synthesize (combine) the separate parts of your analysis into one main idea–your idea about what the poet is trying to say in this poem.

What is the poet trying to say? How forcefully does he or she say it and with what feeling? Which lines bring out the meaning of the poem? Does the poet gradually lead up to the meaning of the poem or does he or she state it right at the beginning? The last lines of a poem are usually important as they either emphasize or change the meaning of the poem. Is this so in the poem that you are analyzing?

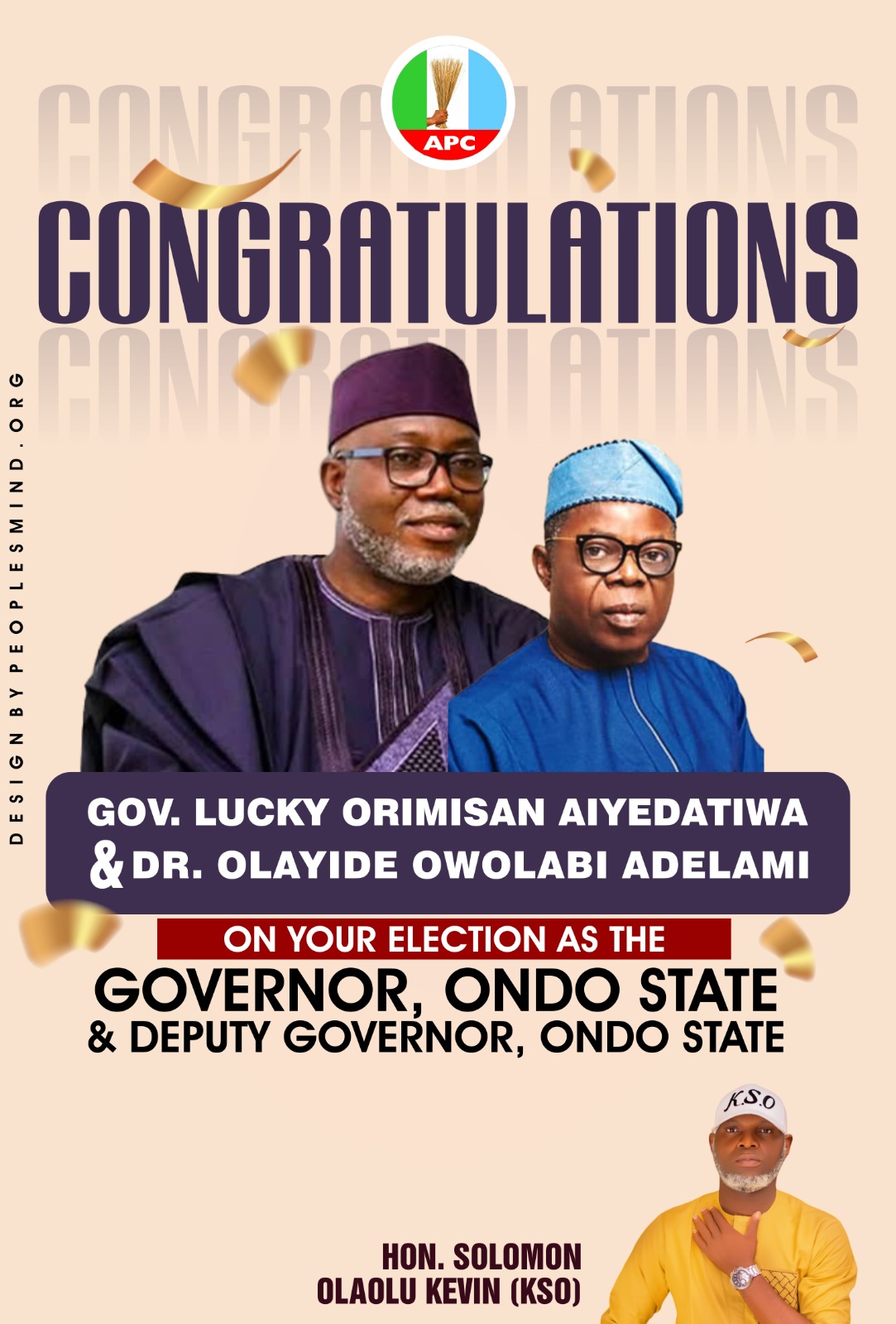

Peoplesmind